Saturday, January 9, 2016

Graceland, and Other Problems

In 1986, Paul Simon released what was widely regarded as one of the albums of the year, if not the decade. Graceland, which debuted at #1 in the United States, regularly topped critical top-ten lists that year; it remained important throughout the rest of the century, appearing as #81 on Rolling Stone's Top 500 Albums of All Time list, as #69 on the Guardian's 100 Best Albums Ever, and on NPR's 300 Most Important Records of the 20th Century rundown. It moved more than five million copies in the US, and went platinum five times over in the UK.

Graceland, which was Simon's sixth studio album, wasn't without its critics. He recorded with South African musicians during an apartheid government; as a result, he was denounced by the ANC for breaking the cultural boycott that had been in effect since the 1950, which was enacted to bring attention to the plight of Black artists living under the regime. While the UN supported Simon—and his stance that he was working with the musicians, not the government—others saw the album as creating solidarity with Pretoria.

The album is a deeply personal expression of loneliness and loss enmeshed withing a global sound. South African musicians like Ladysmith Black Mambazo share billing with American artists like Linda Ronstadt, while the musical influences range from straight-up mbube to N'awlins-flavoured zydeco. Simon fuses these sounds with his own boy-from-New York sensibilities; in the end, Graceland is one of those albums that defines an artist and a moment in time.

Okay, so: why talk about Graceland in 2016?

Because I don't think Graceland could have been made in the 2010s. I don't think Joe Strummer and the Mescalero's excellent 2001 album Global a Go-Go could have been produced in 2016. Our world has become more global and more tuned-in to injustice, both historical and on-going, and we've become more politically correct. We're much more willing to point to cultural appropriation when we see it happening, and say, "hey, that's not right."

But I'm struggling with something: exactly how, in this moment, do I tap into things like hip-hop music, or yoga, or reggaeton, or Asian fusion food, and not seem like I'm stealing something? Globally influenced music produced by white people is one of the easiest things to point to in this category and go "hmmm," but there are lots of others.

Tina Fey was in the news this week when she talked about "opting out" of apologizing for media—in her case, it was the Jane Krakowski-is-a-secret-Native American storyline on last year's Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt. Fey told Net-A-Porter that from now on, her jokes would speak for themselves. This week's episode of movie podcast The Canon focused on Gunga Din, the 1930s swashbuckling adventure set in colonial India—drink every time the hosts said the word "problematic" and you'd be soused before the commercial break—but they spent a lot of time wondering how to fit older, less evolved media into our current understanding of the world. Do we discard it? Do we keep it in the history books, albeit with an asterisk? Jesus, what do we do with Flula's cover of Macklemore's "Thrift Shop"? A uber-white European dude, aping a white Seattle rapper, aping Black hip-hop?

We live in a global world. Hell, Toronto is one of the most diverse places on the planet, and it would be weird to have so many different types of people mixing together all day long without someone influencing the other. But I'm also aware that "mixing" is a relative term here—Toronto still struggles with the ghettoization of immigrants and people of colour, of queer and trans people, of poor people—that creates this false impression of diversity without ever creating real challenges to people's expectations of others. We can pat ourselves on the back for creating Drake, while still allowing Black men and women to suffer the indignities and injustices of racial profiling by police.

I'm a white lady, living a comfortable lifestyle, and I know—I know—that a lot of this could be read as "but I want my yoga class and my Ethiopian food and my hip-hop jams!" But the truth is, I feel a bit frozen. I don't want to be an asshole. I don't want to take, or take over, something that isn't mine. But I also don't want to feel like the only stuff I can believe in in an authentic way has to spring from the potato-girded loins of my Polish foremothers.

When I was in high school, I started getting into hip-hop in a big way. I read books, watched documentaries, listened to dozens of different albums from the late 1970s through to the present. I was fascinated by the genesis of the genre, because when I was sixteen, the idea of being alienated and underrespected, of having no job and no money, of having friends and music and of needing an escape, were things I saw in myself too. I was obviously not running from the cops, or enveloped in a systematically racist society, or living in a drug epidemic, but there was some overlap. It met my emotional needs in a way that, say, N*SYNC did not. And now I wonder, was I being appropriative? Or appreciative?

I want to consume media and culture from the people who make it, not the people who ape it. This seems clear, and morally and ethically okay. For example, buying terrible Native American rip-offs from multinational chains is bogus, and can easily be corrected. (Just buy your Native art from actual Native people, jagoffs.) There are weird blurred lines, like all the Korean-run sushi places on Bloor street, where someone is ripping off someone else, but it's not up to me to get involved. And then there are moments where I just need to stand in solidarity: post the link, make the donation, push for the interview, but know that the community members are leading the actual work under their own auspices and priorities (see: trans* activism, for example, or #BlackLivesMatter).

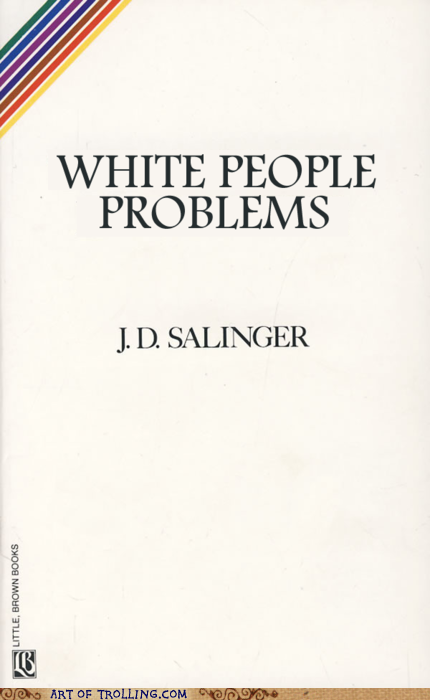

But when there's collaboration and crossover—when Graceland happens—the waters become murky. And I don't really know what to do! Can I appreciate, or participate? Or is my role to stay on the sidelines and witness? This is maybe the only actual instance of "white people problems"—how to move through the world without causing more problems, compounding the sins of the people who look like me, who act like me, who are me.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)