Friday, November 27, 2015

The Best Meal Ever

The best meal I ever had was a potato waffle topped with avocado, salt, and pepper, eaten with a dear friend who would be leaving the next week for a teaching job in America. The best meal I ever had was with my husband, sitting at the floor-to-ceiling window-wall at Luma, eating cod drench in dill all perched atop a bed of pickles. The best meal I ever had was with a friend, when she bought a fake-fruit and ice cream-topped funnel cake from my uncle's beachside snack stand and a half-dozen of us dove on it like seagulls, picking it apart with our bare hands. The best meal I ever had was with my sister and two of her friends at Rundles in Stratford, where, at the ages of 21 (me) and 18 (her), we got roaring drunk and the staff took magnanimous care of us. The best meal I ever had was when my dad and I flew to San Francisco for the weekend, and we got the last table at Chez Panisse, and I ate some kind of soup and some kind of seafood, and then we had to run—run!—back to the BART station in order to take the last train into town.

The New Yorker recently published an article about the process of choosing the world's fifty best restaurants. The list, produced annually by San Pellegrino, started as a lark and has been since elevated into a maker, and marker, of Very Good Restaurants. "According to Bloomberg, the day after Noma captured the No. 1 slot, in 2010, a hundred thousand people tried to book a table," the article says. (Also, an aside, but: has the The New Yorker always been somewhat slutty with its comma use, or is this a new thing?) The list—and it's very tempting to refer to it as The List—has now been subdivided into multiple global regions, like Latin America and Asia. There are gratifyingly few American or French eateries listed; the major culinary earth-shakers are coming from places like Mexico City, Lima, Bangkok and Copenhagen (although the article rightly points out that the sole African entry is run by a white European, which is problematic).

If you are of a certain age, a certain income bracket, and of a certain disposition, you may find yourself treating lists of this kind, both global and local, as a to-do list. One ex-boyfriend was a chef; the other graduated from Starbucks to running the AGO's cafe. I can imagine both of them poring over these articles, scanning for places they've been, places they'll go. The names of the fifty best restaurants are a collection of syllables that reveal nothing about the food they serve: Gaggan, Noma, Arzak. Blank slates, promising the very best in innovative cooking.

As always, lists titled things like, "World's 50 Best Restaurants" create in me an existential despair. I want Canadian cuisine, dammit! What is that, though? Toronto is still dominated by Asian tapas bars, ramen houses, and taco joints. Toronto Life praises Italian seafood restaurants, Asian-Nordic mashups (full disclosure: that sounds like heaven), and Argentinian innovators. With the exception of Boralia, which Toronto Life refers to as a "history lesson," there's often very little acknowledgement of local culinary history, and maybe that's because we simply don't really have one. Toronto, the most diverse city in the country, feels free to borrow extensively from global tastes. What ends up lacking, however, is a sense of our own culinary roots.

What unites the San Pellegrino list is a sense of muscular, embodied gastronomica: a chef's clear vision for his (and it is nearly always a man in the chef's whites, both on this list and in the general population) food. The best chefs in the world aren't offering Spanish food in Moscow or Danish food in Melbourne. If anything, they're maybe hewing a little too close to the locavore movement, sprinkling their plates with "ingredients" like lichen or rainwater. Toronto's chefs make good use of Ontario's produce bounty, the inspiration for the dishes is far-flung indeed. And while Toronto offers really wonderful food, it's not surprising that we have yet to crack the top fifty. The closest we've come has been Langdon Hall in Cambridge in 2010, and they offer carefully Ontarian menu items that sound right at home on the San Pell list: "tasty roots" (featuring an on-trend forest floor broth!) share the page with Montforte chevre and cloudberry souffle. This year, a single Canadian restaurant in Montreal manages to make the top 100.

There is nothing wrong with Toronto's restaurant scene. It's vibrant and innovative, and our fusion menus can compete with anything on offer in Paris, Tokyo, or New York. I've have dozens—hundreds!—of delicious meals here. I could eat Karelia Kitchen's smoked shrimp crepes any day of the week. The rotating seasonal brunch menu Emma's Country Kitchen has exposed me to pumpkin pancakes, and I will never be the same. The small plates at Fishbar, the scallops at R&D, the slobbish (yet carefully constructed) burgers at Burgernator, the mezze plate at Harvest Kitchen: all memorably delicious.

And yet, because I'm greedy, I want more. Doing "other people's food" is safe, in a way: being imperfect can get you a pass, because it's not always possible to offer those flavours to local palates using local ingredients. But creating a cuisine from scratch, building layers of flavour and innovation and tradition, means that failure comes from within; it's a failure to use what comes from your own backyard, your own context, in delicious and novel ways. I want a gang of upstart chefs to create a Dogma 95 for the 416 food scene. I want the excitement to come not from how well we adapt the culinary traditions of the world, but how innovative we can get with our ingredients and traditions, even when we have to create those traditions from scratch. I want to see our name up there on the best-fifty list. It's a beauty pageant, sure; doesn't mean the whole thing doesn't matter.

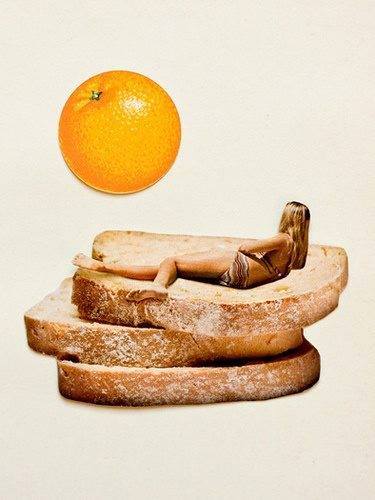

Image via Jose Perez

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)